The Basic Brain Science of Addiction & Recovery

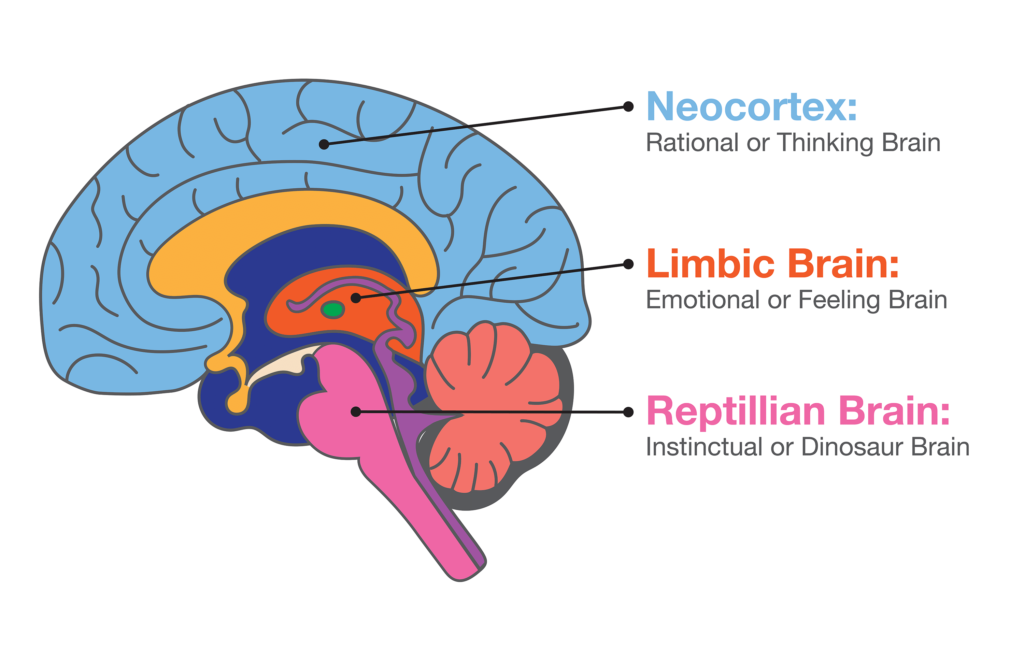

We have two fundamental functions in our brains – not the left-brain/right-brain distinction that contrasts analytical vs. creative expression, rather the function that deals with emotions (and feelings, memory, attention, learning, and behavioral regulation), and the function that deals with reason (and logic, facts, values, goals, critical thinking and decision making).

The emotional part of the brain is sometimes called the limbic or feeling brain – it’s older and less evolved than the reasoning part of the brain (sometimes called the cortex or thinking brain). This feeling brain is closely tied to an even older function called the reptilian brain which deals primarily with instinct.

We’re largely controlled by our feeling (limbic) brain – this is the brain function that deals with feelings and emotions and acts autonomously to ensure our needs are met; the feeling brain has no capacity for language – it doesn’t describe feelings using words. The feeling brain has been (and can be) conditioned to respond in a specific way to certain emotions and feelings; when triggered, the feeling brain responds instinctually and initiates the conditioned response automatically. This happens subconsciously, long before the thinking and reasoning part of the brain is engaged.

The thinking brain is where logic and reason exist and this is where decision making occurs; the cortex (or neo- or pre-frontal cortex) deals with our values and goals and uses language to describe the logic, reasoning, analysis, and critical thinking involved in decision making. This function of the brain can also be conditioned, but most of the thinking that arises happens consciously and is always expressed using language.

What does this have to do with addiction and recovery? It’s now clearly established that addiction disorders involve the brain in essential ways[i], with both structural and functional changes resulting from continued, long-term use and abuse of a substance or behavior. Volumes have been published (including by me[ii],[iii],[iv]) on the brain disease model of addiction; what I’d like to address is the brain disease model as it relates to recovery.

The Half-brained Addict

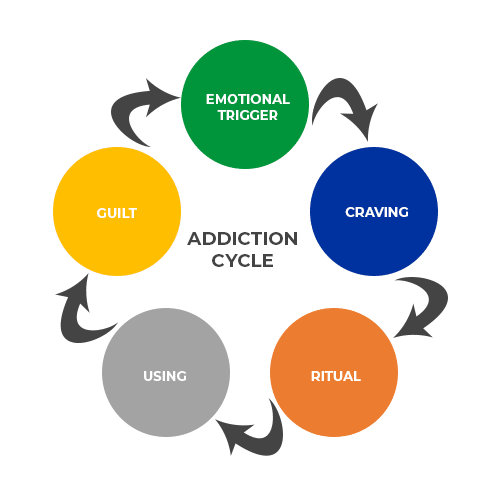

Without casting aspersions on the suffering addict, it’s true that most have become habituated to predominately using only half their brain. Whatever feelings or emotions trigger the addict to use (or act out if a process addiction), over time the feeling brain is increasingly conditioned to respond by reaching for the substance or engaging in the behavior which has effectively assuaged the feeling in the past. The longer this goes on, the more conditioned the feeling brain becomes, and the more instinctual (quick and routine) the response becomes. This is neuroplasticity[v] at its worst.

Unfortunately something else accompanies the habitual conditioning of our emotional/feeling (limbic) brain – the decreasing activation of the thinking (logical, reasonable, consequence-aware) brain. Cycling through the addictive process becomes so well-rehearsed that it becomes automatic – the thinking part of our brain never gets a chance to step in, put on the brakes, and apply logic and reason so a healthy decision can be made in light of known or potential consequences. Part of the recovery process is learning how to interrupt the cycle and, slowly over time, add the thinking brain back into the conversation, at least long enough for the addict to become aware of their destructive process and begin to take steps to stop or alter their course of action.

Is it Addiction or Abuse?

It’s critically important to draw a distinction between a heavy user and an addict – someone who uses drugs or engages in addictive behaviors in an abusive way, and someone who has crossed the line from heavy use to full-blown addiction. There is a difference, and the difference determines what kind of help is required to effect a change. One of my favorite definitions of addiction, and also one of the simplest I’ve heard, is “addiction is a habit that’s become so powerful that the person can’t stop, despite desperately wanting to, and despite severely escalating consequences”.

I’ve collected dozens of different definitions over the years – they’re mostly variations on a common theme, but the one I created above contains the most salient facts for why the person is an addict and not just a heavy user who retains the power to stop if need-be. First, it’s a habit cemented in place through repetition, causing structural and functional changes in the brain. Second, it has the characteristic of powerlessness, where the person has lost complete control over their ability to stop (or not start) – they’re unable to stop despite endless vows and promises, and despite every possible countermeasure designed to prevent them from restarting the cycle. For the true addict, even severe negative consequences, including losing one’s family, job, home, fortune, even one’s freedom, are no longer sufficient to prevent them from using or acting out. The 12-step programs have long used this filter of complete powerlessness to differentiate between a problem user and someone who’s crossed the line into addiction (or alcoholism).

There are countless self-help, group-help, motivational programs and therapies designed to help people get unstuck and change unwanted behaviors; these are largely successful and people benefit in significant ways. If you’ve become a problem drinker, maybe smoke a bit too much pot, have squandered the family’s weekly grocery money at the casino, or been reprimanded at work for sneaking peeks at pornography, these programs are for you. They don’t, however, work for someone who’s crossed the line into addiction. We have decades of evidence to prove this.

For someone wholly addicted to a substance (drugs and alcohol) or behavior (gambling, Internet gaming*, pornography (and sex and love), social media, food, exercise, etc.), self-help and motivational techniques have proven to fall short of breaking the cycle and establishing the person firmly on a path of recovery. What’s required is a more concerted approach which can include hospitalization or in-patient treatment, followed by intensive out-patient therapy and follow-up over an extended period of time.

* The American Psychiatric Association is considering Internet Gaming, Sex and Pornography as possible disorders; they are mentioned in the DSM-5 but not yet fully adopted with diagnostic criteria and prescriptive treatments.

The fundamental mechanism to jumpstart recovery is to first interrupt the addictive cycle; if substance-based, detox is the first step (sometimes monitored, as detox and withdrawal can be life-threatening) followed by intensive in-patient or out-patient therapy or treatment. If behavioral, direct removal from the patient’s current situation in the form of a leave of absence from work or temporary separation from spouse or family may be necessary to create a significant space where healing can begin. This separation may be in the form of an in-patient treatment center or potentially a sober living home while the patient attends intensive out-patient treatment.

Two things to note here: first, notice I’ve referred to the addict as a patient; addictions or “use disorders” as they are increasingly called are considered a brain disease – a legitimate illness which can be effectively treated, and not a moral weakness or corruption. According to Dr. Nora Volkow, Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), “brain disorder[vi]” is a term which now acknowledges that “addiction is a chronic but treatable medical condition involving changes to circuits involved in reward, stress, and self-control”. Second, while hospitalization, admittance to (short- and long-term) treatment centers, and access to intensive in- and out-patient therapy are effective at establishing a recovery foothold, these avenues are simply not available to every struggling addict. For the uninsured or under-insured, expensive treatment centers and intensives are unaffordable. Fortunately there are other options but establishing a solid foundation of recovery without formal treatment or therapy can be more difficult.

Pickles in Recovery

Whether the addict has come through treatment or not, the process for full recovery is, over time, essentially the same. In the simplest terms, it’s:

- interrupt the feeling brain’s using or acting out process and help the addict become stable enough to begin to do some work – this unfortunately can be brutally hard, especially with drugs like meth and heroin, and with process addictions like gambling and sex addiction

- begin to help the addict see the true nature of their disease along with their powerlessness to stop on their own – if they could they already would have – having help increases the odds of success significantly – it’s also been shown that addicts helping other addicts is beneficial

- come clean with a full accounting of the good, the bad and the ugly – keeping secrets keeps addicts sick, in fact there’s a saying “you’re only as sick as your secrets” – what we hold back is what holds us back; this accounting is done with a trusted friend or advisor, and many addicts say telling their full truth lifts an enormous weight off their minds and shoulders

- clean up the messes and repair what’s been broken – this is a critical piece of recovery – many addicts have a long history of ruined relationships, broken trusts, and other damages resulting from their years or even decades of illness – making amends and trying to make things right is paramount to being able to put our messy past behind us

- begin to address the things that started the addiction to begin with – addiction science continues to evolve and findings increasingly point to trauma, shame and psychological conditions as a root cause of use disorders – it’s also known that epigenetics, environment and socio-cultural influences play an important role in the formation of addictions (why one person becomes addicted while another uses with immunity)

- continue to heal and learn to deal with life on life’s terms – the ability to be at peace and accepting of every situation life presents without the need to escape or mask strong emotions – addicts become entrenched in a fantasy world and it takes time to reground in reality

Regardless how an addict got started – recreational use, curiosity, social pressure, etc., they eventually turn to their drug (or behavior) of choice to artificially create pleasure or escape pain; they learn to believe the lie “this is what I need” or “this will solve the problem” or “this will make me feel better” or unfortunately “this time will be different” (it never is). Through repetition, the cycle of addiction acts to cement this fantasy thinking and it can be significantly difficult to break the cycle and establish recovery-centered thoughts, behaviors, practices and principles as the person’s new way of living. It’s in these – the thoughts, behaviors, practices and principles that we re-engage our thinking brain as an ally to pull us out of the feeling brain’s reflexive and deeply habituated thoughts and behaviors.

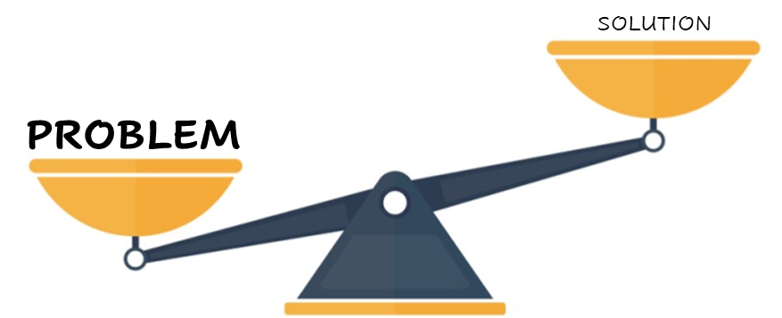

I like the saying “continuous recovery requires continuous effort”. Far too many people get a few days, weeks, months or even years of recovery and think “OK, I got this, no problem”, then relapse. Others get into recovery and, once they’ve achieved a bit of freedom from their addiction, become complacent and stop doing the work necessary to not just recover, but to heal and learn a different way of being in the world without their crutch. Usually these people also relapse or, at a minimum, are miserable trying to navigate life without recovery practices and supports. For both groups I use the analogy of a set of scales, and the delicate balance between living in the solution or living in the problem – a problem that never actually goes away.

According to NIDA[vii] “like other chronic diseases such as heart disease or asthma, treatment for drug addiction usually isn’t a cure”. My personal experience over 40 years of continuous sobriety validates that; I’ve lost count of the friends I’ve made in recovery who, after many years and even decades of sobriety, turned back to their drug (or alcohol or behavior) and picked up right where they left off when they’d previously stopped. Although many dislike and disagree with the statement “once an addict, always an addict”, experience proves that once an addict has crossed the line from user to addict, there’s no going back. There’s a saying in the 12-step program “once a pickle, never again a cucumber” – that’s based on the program’s first-hand experience of recoverees trying to go back to recreational using, only to fail miserably. Again, my personal experience supports this conclusion, as I’ve witnessed countless people get clean, then try and go back to being a “normal” user – and fail.

Tipping the Scales in Our Favor

I’m frequently asked, “why is it so hard to break free of my addiction and the resulting problems in my life?”. For many, recovery isn’t just about getting sober or clean from drugs and behaviors – there’s a whole world of trouble attached to our addictions, and these troubles need to be addressed. Getting clean and learning to stay clean is the first step; repairing damage from our past and learning to live without having to mask or drown our feelings represents all the necessary work that follows. My answer to the above question is “because all you know is the problem – you haven’t yet learned the solution and have no experience practicing or living with it”. The problem weighs you down as shown visually in the analogy of the scales. Learning what the solution is and learning to live with and in the solution takes time and lots of practice. Mistakes will be made and there will be many slips into old thinking and behaviors.

Two of my favorite quotes from the book Alcoholics Anonymous (the primary text of the program of the same name) are “when I stopped living in the problem and began living in the answer, the problem went away” and “if I focus on a problem, the problem increases; if I focus on the answer, the answer increases” (pp.417, 419). These are great quotes and the visual analogy of the scales can be useful when recoverees become impatient, frustrated or even discouraged at the slow churn of recovery. Slowly over time the solution becomes clear, answers come (different for each recoveree), strength and confidence return, and life becomes increasingly frictionless as the addict learns how to be their authentic self in a challenging world. No more hiding behind a façade out of fear of being known for who we are. No more need to mask or drown our feelings – we instead learn how to understand and control our strong feelings and be at peace with them without judgement or wishing they were different. This is our solution as recovering addicts – learning to be genuine and authentic in every situation and with every person, and capable of handling our strong emotions without hiding behind a substance, behavior or mask. Eventually the scales tip and the solution becomes our normal, default way of being with ourselves and with the world.

Recovery is the practice we have to change our lives and become the people we’d hoped to be. Recovery isn’t done in isolation; recovery is best done in community with others, either on the same path or who have been where we are and come out the other side. Every time we help someone on their recovery journey (and sometimes that just means listening to them), we add to our solution and our scale tips. Every time we allow someone to help us on our journey, our solution expands and our scale tips. The farther we get from active addiction, the better we’re able to maintain balance between our thinking and feeling brains. We need our feeling brain – we just don’t need it to run roughshod in response to triggers, temptation or strong emotions before our thinking brain has had a chance to step in, quiet the moment, slow things down, and do what it does best with logic, facts, our values, goals, critical thinking and decision making. While science and experience tell us our addictive problem never goes away, we can tip the scales heavily in our favor by embracing recovery and joining others in an active thinking and feeling recovery community.

Endnotes

[i] Volkow ND, DHand, et al. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction: NEJM [Internet]. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016; Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

[ii] Barnard, Steve. February 2021. The Opposite of Addiction. https://narrativescoaching.com/the-opposite-of-addiction/

[iii] Barnard, Steve. June 2021. The Porn Addicted Brain. https://narrativescoaching.com/the-sex-addicted-brain/

[iv] Barnard, Steve. March 2022. Porn: The Pernicious Predator. https://narrativescoaching.com/porn-the-pernicious-predator/

[v] O’Brien C. P. (2009). Neuroplasticity in addictive disorders. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 11(3), 350–353. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/cpobrien

[vi] NIDA. 2018, March 23. What Does It Mean When We Call Addiction a Brain Disorder?. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2018/03/what-does-it-mean-when-we-call-addiction-brain-disorder

[vii] NIDA. 2022, March 22. Treatment and Recovery. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/treatment-recovery on 2022, April 15